Brooke Hiers looking at the lot where her house used to be in Horseshoe Beach, Florida. Associated Press.

For the third time in 13 months, this windswept stretch of Florida’s Big Bend took a direct hit from a hurricane — a one-two-three punch to a 50-mile sliver of the state’s more than 8,400 miles of coastline, first by Idalia, then Category 1 Hurricane Debby in August 2024 and now Helene.

It was just a month ago that Brooke Hiers left the state-issued emergency trailer where her family had lived since Hurricane Idalia slammed into her Gulf Coast fishing village of Horseshoe Beach in August 2023.

Hiers and her husband Clint were still finishing the electrical work in the home they painstakingly rebuilt themselves, wiping out Clint’s savings to do so. They never will finish that wiring job.

Hurricane Helene blew their newly renovated home off its four foot-high pilings, sending it floating into the neighbor’s yard next door.

“I’ve hugged people, and cried with them. But this is the first time I’ve really sat down here and been here and thought about it. I’ve tried to use them all. Hiers said.

For the third time in 13 months, this windswept stretch of Florida’s Big Bend took a direct hit from a hurricane — a one-two-three punch to a 50-mile sliver of the state’s more than 8,400 miles of coastline, first by Idalia, then Category 1 Hurricane Debby in August 2024 and now Helene.

Hiers, who sits on Horseshoe Beach’s town council, said words like “unbelievable” are beginning to lose their meaning.

“I’ve tried to use them all. Catastrophic. Devastating. Heartbreaking … none of that explains what happened here,” Hiers said.

The back-to-back hits to Florida’s Big Bend are forcing residents to reckon with the true costs of living in an area under siege by storms that researchers say are becoming stronger because of climate change.

The Hiers, like many others here, can’t afford homeowner’s insurance on their flood-prone houses, even if it was available.

Residents who have watched their life savings get washed away multiple times are left with few choices — leave the communities where their families have lived for generations, pay tens of thousands of dollars to rebuild their houses on stilts as building codes require, or move into a recreational vehicle they can drive out of harm’s way.

The sparsely populated Big Bend is known for its towering pine forests and pristine salt marshes that disappear into the horizon, a remote stretch of largely undeveloped coastline that’s mostly dodged the crush of condos, golf courses and souvenir strip malls that has carved up so much of the Sunshine State.

This is a place where teachers, mill workers and housekeepers could still afford to live within walking distance of the Gulf’s white sand beaches. Or at least they used to, until a third successive hurricane blew their homes apart.

Helene was so destructive, many residents don’t have a home left to clean up, escaping the storm with little more than the clothes on their backs, even losing their shoes to the surging tides.

In the surreal aftermath of this third hurricane, some residents don’t have the strength to clean up their homes again, not with other storms still brewing in the Gulf.

With marinas washed away, restaurants collapsed, and vacation homes blown apart, many commercial fishermen, servers and housecleaners lost their homes and their jobs on the same day.

Those who worked at the local sawmill and paper mill, two bedrock employers in the area, were laid off in the past year too. Now a convoy of semi-trucks full of hurricane relief supplies have set up camp at the shuttered mill in the city of Perry.

Hud Lilliott was a mill worker for 28 years, before losing his job and now his canal-front home in Dekle Beach, just down the street from the house where he grew up.

Lilliott and his wife Laurie hope to rebuild their house there, but they don’t know how they’ll pay for it. And they’re worried the school in Steinhatchee where Laurie teaches first grade could become another casualty of the storm, as the county watches its tax base float away.

“We’ve worked our whole lives and we’re so close to where they say the ‘golden years’,” Laurie said. “It’s like you can see the light and it all goes dark.”

Dave Beamer rebuilt his home in Steinhatchee after it was “totaled” by Hurricane Idalia, only to see it washed into the marsh a year later.

A waterlogged clock in a shed nearby shows the moment when time stopped, marking before Helene and after.

Beamer plans to stay in this river town, but put his home on wheels — buying a camper and building a pole barn to park it under.

“I feel so bad for everybody. And everybody says, I’m sorry. I’m sorry and everybody’s sorry. And now it’s time to go back to work and let’s get’er done.”

RELATED:

What to know about Hurricane Helene and widespread flooding the storm left across the Southeast US

Political grudges, conspiracy theories could undermine disaster relief under Trump

Donald Trump’s history of punishing disloyalty and Republicans’ amplification of conspiracy theories could undermine disaster relief efforts if...

‘Document everything’: Your 10-step guide to insurance claims after Hurricane Milton

Before Milton's arrival, experts had warned that it could cause billions in losses, further damaging the state's already troubled insurance market....

Florida’s wildfire season: What you need to know

Discover Florida's year-round wildfire risks, contributing factors, and prevention strategies, plus key historical events and community awareness....

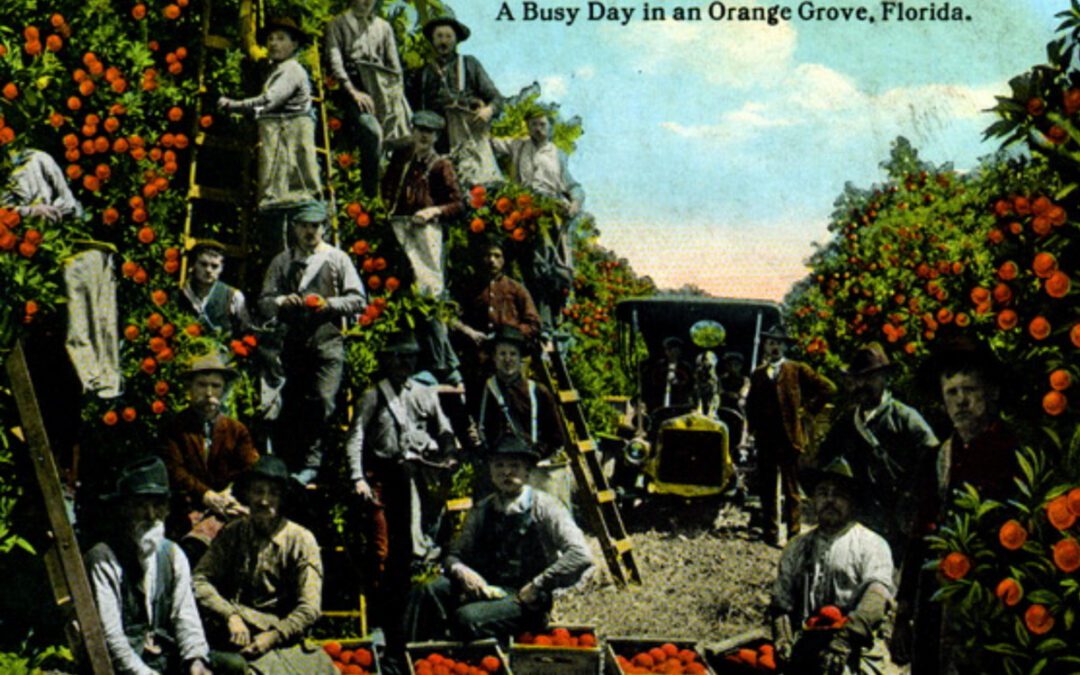

Decline of Florida’s citrus industry hastened by Trump’s tariff tiff

Hurricanes and disease have already taken a tremendous toll on those fragrant trees, not to mention development demand for the land. This weekend I...